Is there anyone who feels more like an outcast than a Vietnam vet?

Is there anyone who feels more like an outcast than a Vietnam vet?

When Moncho, a twenty-three year old soldier, returned from Vietnam to his home in Puerto Rico after two years of obligatory service, he was greeted not by applause and acceptance but by jeering and hatred.

For forty years, Moncho lived with that hatred. He became a dark, violent man, plagued by nightmares and self-loathing. He turned to alcohol to numb the pain, destroyed two marriages, and tortured himself in worse ways than the enemy ever could have. Mentally broken, Moncho lived angry and ashamed. He hated himself for the things he needed to do to stay alive.

“I’m a killer,” he told himself, over and over again—until he believed it.

Everyone was the enemy. He lived perpetually scared, afraid that someone might kill him, like he had killed. In Vietnam he was a Tunnel Rat, crawling through narrow passageways, looking for enemy fodder. On his return to Puerto Rico, he hid in the foxhole of his fears. Hatred was his companion, rage his sustenance. He ate, breathed and drank hatred and rage. And the more he hated, the better he felt because hatred—self-hatred—was his punishment. He thrived on the power he found through hate. Hatred gave him strength and he became addicted to it. People feared him. He looked mean, maybe even crazy. But inside, he was burdened with shame and guilt. When he wasn’t mad, he was sad. And he had no idea how to stop the torment.

For many years, Moncho was haunted by nightmares, by the memory of Vietnamese soldiers who—for a fraction of a second—had let down their guard—and paid for it with their lives.

The blood of his enemies stained his life.

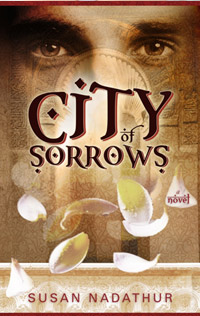

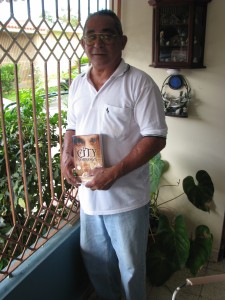

Moncho has spent the last forty years trying to clean that stain, to find that young man who left Puerto Rico for Vietnam and returned changed. He found part of that young man in Diego Vargas, the nineteen-year-old Spanish Gypsy protagonist of the novel City of Sorrows by Susan Nadathur.

Like Moncho, Diego hated and blamed himself for something bad that happened in his life. He hated all Spaniards because one Spaniard took away all that was dear to him. Diego believed that he did not deserve to be happy, that revenge was the only option. The doors to healing were opened for him, but he chose not to walk through them. Like Moncho, Diego thrived on his hatred and his pain.

But then Diego met Rajiv, a young man from India, who saw that there was something wrong with Diego and wanted to help. Without being obvious or asking Diego to spill out his story, Rajiv found the way to get through to Diego. And through this unlikely friendship between an East Indian immigrant and a Spanish Gypsy, the road to healing began. But it wasn’t until Diego was able to forgive not only the man who had wronged him but himself as well, that he finally was capable of seeing the light.

Moncho has also seen the light. He has finally understood that when you forgive and love yourself, you can forgive and love others as well.

“Love is our savior,” Moncho says. “And God’s love is meant to be shared.”

And share it he did. For years Moncho had been scared of the dark. He never dared go out past sunset, fearing what lurked inside the shadows. But on April 19, 2013, Moncho accompanied his grandson to San Juan on a bus from Lajas. His purpose: to attend the book launch for City of Sorrows in La Casa de Espana. The bus left while it was light. But, Moncho knew that it would return in the darkness of night. He wanted to go anyway, to share his story.

Hopefully, Moncho was able to see that young man again in one of the mirrors in the Hall of Mirrors where the event took place. And maybe now, he no longer feels like the outcast he became when life did not turn out the way he had planned.