Despite being the literal embodiment of evil, Lucifer — or Satan or Beelzebub or whatever you chose to call him — has fascinated poets and authors since words were first put down on paper. I plead guilty to the same. Lucifer intrigues me. Not in an evil-I’m-going-dark-kind-of way, but as a literary device that can help me define what evil is, and more importantly, how it can be conquered. If we identify Lucifer as being the sole cause and root of all evil, it allows that evil to be interpreted. Some of the best and most creative interpretations are now immortalized in some of the greatest pieces of literature of all time. Like many writers before me, I have studied — and been inspired — by much of this great work.

Over the next several posts, I’d like to share with you five classic characterizations of Satan in world literature and show you how those characterizations influenced my writing. Literary Lucifers have changed drastically over the centuries. From Dante Alighieri’s three-faced Satan trapped in ice to Neil Gaiman’s surprisingly likeable Lucifer Morningstar, each characterization has taken on a life of its own life and continues to live on in the cultural history of the countries that inspired them. Often charming and always compelling, here is the first of five of the most iconic devil portrayals in both classic and modern literature.

Dante Alighieri’s Dis (Inferno, 1472)

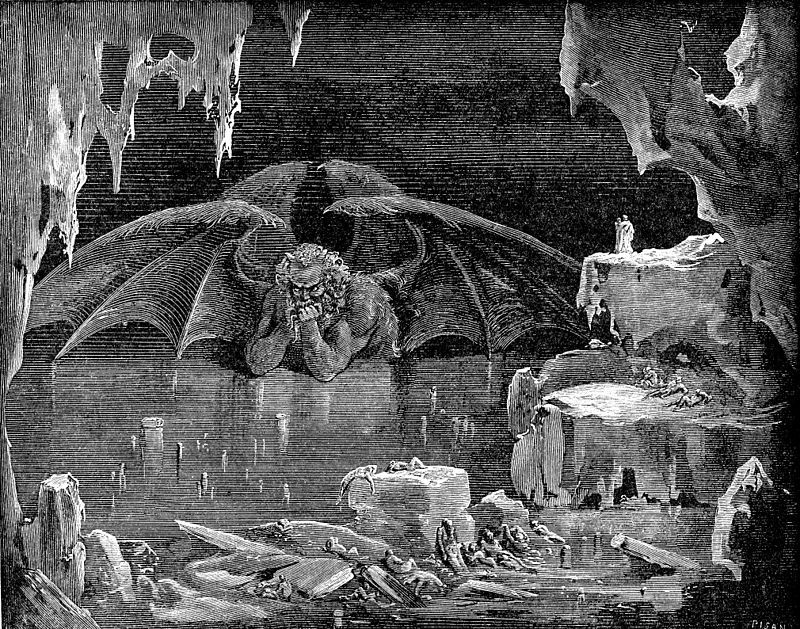

The Lucifer in Inferno is called Dis, in reference to the Roman god of the Underworld. Trapped waist-deep in a frozen lake at the very bottom of the ninth circle of Hell, Dante’s version shows Lucifer being as much a victim of Hell as the other damned souls suffering beside him. Far from running the show, Dis is just another prisoner.

In contrast with some of the more human portrayals in literature, Dis’s true form is colossal and beast-like. His appearance is monstrous, with great tufts of fur and six huge, bat-like wings. He has three heads (thought by many to be a mockery of the holy trinity), each of which are eternally gnawing on the souls of Judas Iscariot (Christ’s betrayer), Brutus and Cassius (Julius Caesar’s murderers). Like these three sinners, Lucifer is trapped in Cocytus, the ninth and final circle of Hell, the circle reserved for the treacherous and traitorous. In the words of the poet, “He weeps with all six eyes, and the tears fall over his three chins mingled with bloody foam.” His wings beat in an eternal struggle to escape his frigid prison, yet the winds that his wings create only ensures that he is trapped even more solidly beside every other soul in Cocytus. Dante’s Dis is not a happy guy.

Unlike most depictions of the devil, Dis is associated with extreme cold instead of fire. His lake is frozen, and the beating of his wings creates an icy wind that is felt throughout all the other circles of Hell. This icy cold epitomizes the absence of love and warmth and life at the very heart of Dante’s frozen universe.

What I learned from Dante’s Lucifer:

In Dante’s Lucifer, Dis embodies the Augustinian idea that evil is the absence of good. In the Inferno, Dante gives shape to Augustine’s idea that there is no transcendent principle of evil. His representation of Lucifer is an attempt to make the point that evil is not something, but the lack of something: evil is the absence of good. Dante’s Lucifer breathes un-love just as God breathes the warm breath of love. In Dante’s Inferno, Lucifer is trapped in a frozen pit devoid of everything that makes us human: love, warmth, goodness, and ultimately — life. Dante’s Lucifer transitions from absolute beauty before The Fall to absolute ugliness. He is neither dead nor alive. But nor is he powerful. Rather than being a force to be feared, he is a creature to be loathed, or possibly, even pitied.

How much of Dante’s Lucifer is in my Lucifer?

In my soon-to-be-released Young Adult novel, Mind Binder (Book 1 of The Halls of Abaddon series), my Lucifer (called Lucius) shares no physical resemblance to Dis. Lucius is not an ugly monster trapped in ice, but rather a charismatic being in the form of a human man. As Jadiel, the protagonist, says of him, “The Lucius I once met as a boy was exciting. Creative and bold. A dark romantic rebel. One day when I was ten, my parents introduced me to him. From the moment I met him, I idolized him. I wanted to be like him. He was the ultimate poetic anti-hero. Stirring up rebellion. Planting new ideas into tired minds. It was all so insanely intellectual — until I came to the painful realization that there was no love or goodness in him.”

Like Dis, Lucius is frozen into an icy coldness completely devoid of human warmth. He is chilling in his demeanor, with a voice that sounds like a cracking glacier calving into the Arctic Ocean.

Questions for Thought

- Should the imagination of authors be allowed to shape a reader’s perception of who Lucifer is, and what he might look like? Words hold power, but should they?

- According to Dante’s world view, what does the lowest part of Hell look like? Does the landscape surprise you? What did you expect? How is it an appropriate place for punishing the sinners who are found here?

- In Dante’s Inferno, what does Lucifer look like? How is he placed at the bottom of the pit? Is there anything about Dante’s Lucifer that surprises you?

- How would you describe Lucifer in your own novel or poem? What works of literature have inspired your description?

0 Comments